If ChatGPT were let loose in an emergency department, it might recommend unnecessary x-rays, prescribe antibiotics for patients who don’t need them, or admit individuals who don’t require hospitalization, according to a new study from UC San Francisco.

The researchers emphasized that while the model’s responses can be refined through specific prompts, it still falls short of the clinical judgment of a human doctor.

“This is an important reminder for clinicians not to place blind trust in these models,” said lead author Chris Williams, MB BChir, a postdoctoral scholar, in the study published Oct. 8 in *Nature Communications*. “ChatGPT can answer medical exam questions and assist with drafting clinical notes, but it isn’t designed for situations that require multiple considerations, like those in the emergency department.”

Previously, Williams demonstrated that ChatGPT, a large language model (LLM) being explored for clinical AI applications, performed slightly better than humans in identifying which of two emergency patients was in more critical condition, a straightforward decision between patient A and patient B.

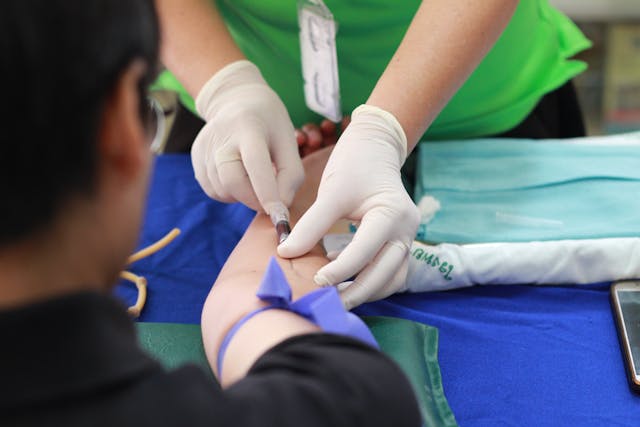

In the current study, Williams pushed the AI further by asking it to make more complex decisions typical of an emergency department, such as determining whether to admit a patient, order x-rays or other scans, or prescribe antibiotics.

AI falls short of resident physicians

To evaluate the AI, the researchers compiled 1,000 emergency department visits from an archive of over 251,000 at UCSF Health. These visits were balanced to reflect the actual ratios of “yes” and “no” decisions made by clinicians regarding admissions, radiology, and antibiotics.

The research team entered doctors’ notes detailing each patient’s symptoms and physical exam findings into ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 using UCSF’s secure generative AI platform, which adheres to strict privacy protections. They then tested the accuracy of the AI’s recommendations using increasingly detailed prompts.

Across the board, the AI models were more likely to recommend unnecessary services. ChatGPT-4 was 8% less accurate than resident physicians, and ChatGPT-3.5 was 24% less accurate.

Williams suggested that the models’ tendency to overprescribe could be due to their training on internet data, where health advice often errs on the side of caution, encouraging users to seek medical attention.

“These models are almost conditioned to say, ‘consult a doctor,’ which is a safe recommendation for the general public,” he explained. “However, in the emergency department, erring on the side of caution can lead to unnecessary interventions, which may harm patients, strain resources, and increase costs.”

Williams noted that for AI models to be truly useful in the ED, they will require better frameworks to assess clinical data. The designers of these frameworks will need to strike a careful balance: ensuring the AI catches serious conditions without over-recommending tests and treatments that may be unnecessary.

This challenge will require researchers developing medical AI, along with clinicians and the broader public, to carefully consider where to draw the line between caution and over-intervention.

- Press release – University of California – San Francisco